A Gilded Age Affair Cover-Up

Charles Hanson Towne (1877-1949) was a prolific author, poet and editor of such prestigious magazines as Smart Set, Delineator, McClure’s, Designer, and Harper’s Bazaar.

As an urbane New Yorker, Towne’s hobnobbing with celebrities in literature, stage, politics and society was de riguer. His acquaintances also gave him access to juicy gossip.

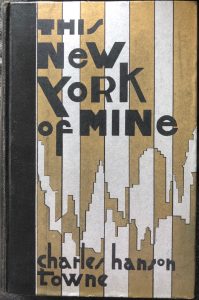

In the second of Towne’s memoirs (he wrote three), This New York Of Mine, Cosmopolitan (1931), he relates an apocryphal story which occurred at the turn-of-the-century that Towne claims is true.

In the second of Towne’s memoirs (he wrote three), This New York Of Mine, Cosmopolitan (1931), he relates an apocryphal story which occurred at the turn-of-the-century that Towne claims is true.

There are no names attached to the tale. But if the facts are correct an online detective could figure out who the noted protagonists are. There are enough clues to match the story to the specific actress and her lover.

From, This New York Of Mine:

Yes, there were beaus and belles; and personalities, too; and strange stories floated about the city. If one thinks that romance did not flourish then; that a woman’s name was not protected; that mysteries were not hushed up then, as now, listen:

Down on lower Fifth Avenue there dwelt a highly respected gentleman. He and his wife were among the very first to be listed among the noble Four Hundred. But like many another gentleman of his middle years, he had taken unto himself a mistress. And one summer when his family were absent in Newport, he remained in town for a week, business being the excuse.

But of course the real reason was that he wished to see as much as he could of the actress he adored before she sailed for Europe—at his expense—a few days later.

And so it was that while New York—a much less crowded city at that time—drowsed in the heat of a sultry July night, practically a deserted village, Mr. Blank and his mistress were alone in her apartment, then far up-town in the West Fifties. There were few uniformed doormen and ubiquitous bellboys in those quiet days, and on such a night as this, in the very heart of summer, an almost bucolic hush lay over the city. A hansom lurched —against the arc-lights down on the corner, and tired. horses pulled the empty cars up and down Sixth Avenue

and Broadway.These two were happy and serene 1n each other’s company, yet wistfully sad over their approaching separation. They had no premonition of how close their eternal separation would be. For at midnight the man dropped dead, clothed only—grotesque and anticlimactic as it must sound today—in his nightshirt.

Horror seized the actress when she realized that her lover, so highly regarded in the community, lay motionless in her bed. She too was well-known in her world. It would never do—it could not be—that a scandal should occur. One can picture her, alone, distracted, horrified, feeling New York’s hot breath pouring in at her windows; sensing that aching silence of the Streets, as the great monster of the city turned slowly in its sleep.

She thought rapidly. She must have help—but not the paid help of the servants in the building. She remembered two men-about-town whom she had known in the past, and known well. They were still her friends. One was a doctor, and she knew he was in town, living at his club. He might be there. With trembling hands she reached for the telephone. An awful moment of suspense. The night operator’s sleepy voice at the club. “I’ll see if he’s in.” Silence. And then, in her panic, she heard his answer, roused from slumber. “Who is it?” he said.

She told him to come to her at once. “I am ill—desperately ill,” she whispered over the wire. And she added, “I need you.”

Within ten minutes he was at her door. And he saw a woman, white, terrified, but in full control of her emotions, since she had to be calm until she put through her desperate plan.

“You must take him out of here. You must dress him, and take him down the stairs, and in a cab to his home. His keys are in his pocket. If anyone sees you, you must pretend that he is drunk. It’s awful. But it must be done. Then you must take him into that house, undress him, and put him in ‘his own bed, and come back here to tell me that you have done it. Oh!” And for the first time she sobbed.

“Be calm. I see it all. Yes, I’ll do it,” said the doctor, “You know you can trust me.”

He set about his grim business. Down the stairs he carried his awful burden. Fortunately, the one servant on duty was asleep in the basement. On the sidewalk he hailed the one open fiacre which chanced to loll down the street. The unsuspicious driver was glad of any fare at this late hour. “Just one more drunk being carried home,” he thought. He was used to such experiences.

And to that proud door on lower Fifth Avenue the dead man was taken, and the cabman dismissed.

The next evening, the papers told how the respected and respectable Mr. Blank had been found by the house-keeper who came in to prepare his late breakfast, dead of heart disease in his bed. And for years no one, in all our town, knew the true story of that terrible night. The actress died—long afterward, abroad ; and columns were printed about the perfection. of her art, and regret was expressed that she had retired from our stage at the height of her career.

New York is throbbing with such stories, if one could dig beneath the surface of the life of our town.

If you have any ideas who the people are, leave a comment with any evidence.

The search continues…

I Googled “late 19th century american actress died in Europe”. This came up:

“Adah Isaacs Menken (June 15, 1835 – August 10, 1868) was an American actress, painter and poet, and was the highest earning actress of her time. She was best known for her performance in the hippodrama Mazeppa, with a climax that featured her apparently nude and riding a horse on stage.”

Riding nude on a horse sounded like she was a good bet. She died in Paris, age 33, of tuberculosis. Nothing about a rich lover on 5th Avenue, though.

Good try, but can’t be. This had to occur in the late 19th / early 20th century. She makes a telephone call.